- Home

- Yehuda Avner

The Ambassador Page 2

The Ambassador Read online

Page 2

“I cannot let it go, Herr Gottfried,” the Gestapo officer said.

Gottfried stared at the man. His jaw shook. He couldn’t speak.

Perhaps if he confessed, the Nazi would shoot him and all this suffering would simply be over.

“You have failed to pay certain charges due to the Reich, Herr Gottfried.” The Gestapo man rubbed his hands together and opened his palms.

Gottfried shook his head. “I…I don’t—”

“He wants his bribe,” the youngest of the warehouse hands called out.

The others smiled.

“Come on, pay him,” the young man said. “We were supposed to knock off shift ten minutes ago.”

Gottfried pulled out his wallet. He fumbled for his last twenty-five reichsmarks, about enough for a good bottle of wine.

The Gestapo man sneered and twitched his fingers. He wanted more.

Gottfried stammered, “I have no other money. It’s all been—”

“All been what?” The Gestapo man was close. Cigarette breath and a bratwurst belch hit Gottfried’s face.

He would’ve said stolen, because the process of emigration for a Jew after only one year of Hitler’s rule was simple theft. Taxes and levies and duties. Whatever they were called, they were no different from the greedy hand the Gestapo man extended now.

“Open that box.” The officer pointed at the young warehouse worker and then at one of Gottfried’s crates. “Number 3.” Gottfried felt his lungs seizing up, his heart thundering.

“What for? It’s been checked, Kumpan.” The worker grinned insolently.

Kumpan was what communists called their buddies. The Gestapo sent communists to concentration camps.

“Take his overcoat or something if he doesn’t have any cash. You don’t need to be shy about it. He’s only a Yid.”

“Open it.”

The worker shrugged and set to work on the seals of the crate with a crowbar. “I’m supposed to meet a girl, you know. You’re going to let a few marks come between a man and some nice ass?”

“Shut your face.”

The worker mumbled something just as the lid of the crate lifted. The other men laughed loudly. They fell silent as the Gestapo officer stalked toward them.

“What did you say?” he growled.

“You wanted it open. It’s open.”

“Repeat what you said.” He poked the worker with his finger, then gave him a harder shove with his clenched fist.

The young man wasn’t going to back down now. One of the other workers reached to restrain him, but he shrugged free. “I said, that thing below your hat is proof that not everything with two cheeks is a face.”

The Gestapo inspector laughed. He stepped back from the worker, shaking his head, acknowledging the low wit of the remark.

The young man grinned at his comrades, relaxed. He had put one over on the secret policeman.

In a flash the officer seized the crowbar from the worker’s hand. He swung it hard into the man’s jaw, then into the back of his skull with vicious, frenzied blows. The man dropped to his knees. The Gestapo officer hammered the end of the bar down on the crown of his wavering head. The man’s skull crunched like an egg under a spoon. A spray of gore squirted across Gottfried’s pine crate.

Panting, the Gestapo man snarled at the other workers. “Shut this crate, you pair of shits.” He tossed the bloodied crowbar inside, where the unseen Stradivarius lay.

Gottfried reached for the wall for support, quivering and faint. The Gestapo man grabbed the thin wad of reichsmarks from him. “Go on, fuck off. Before I decide it was you who killed this shitty Commie.”

Gottfried rushed back to the train. His stomach churned and his guts felt like they were in flames. He threw himself into the bathroom, dropped his pants, and sat on the toilet just before he truly lost control of himself. As the train jerked into motion, he drained his bowels, weeping and shuddering. After some time, his stomach settled. He cleaned himself up and went to his seat.

The ticket-collector entered before they were out of the Berlin suburbs. He took Gottfried’s ticket and frowned.

My God, what now? Gottfried thought.

“Are you hurt, Mein Herr?” the conductor asked.

Gottfried shook his head.

The railway man gestured to his face. “You’re bleeding.”

Gottfried snatched his handkerchief and rubbed at his face. The linen came away smeared with the blood of the man the Gestapo officer had murdered.

Part I

The time cannot be far distant when Palestine will again be able to accept its sons who have been lost to it for over a thousand years. Our good wishes together with our official good will go with them.

Das Schwarze Korps, SS newspaper, May 15, 1935

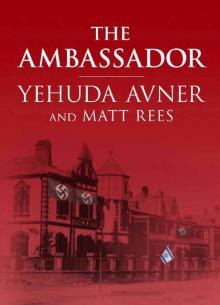

A Templer-owned hotel, home of the German consulate in Jerusalem, 1933

Chapter 1

Palestine, 1937

Dan Lavi watched his wife from the kitchen. Curled up in a deep armchair, her big almond eyes shut, she was lost in the music from the phonograph. He felt a surge of love in his chest that seemed truly physical to him, like a warm wave rushing into Tel Aviv beach. Anna moved her hand gently, conducting, as the soloist went into a striking cadenza.

Dan ran the hot water over the dinner dishes in the sink. “That violinist is amazing. Even with my tin ear I can hear it. Who is it?”

“Wilhelm Gottfried. With the Berlin Philharmonic. Mendelssohn’s concerto.”

“You don’t say? I’m supposed to be going to a concert by him this week. Gottfried’s playing with a new orchestra that’s been formed here in Jerusalem.”

“You’re going? What about me? I adore Gottfried.”

“You’re always too busy to join me on these official engagements. I didn’t think you’d want to come.”

“Can I help it if little children get sick and need their pediatrician? But you’re right. I don’t have time.”

Dan watched as his wife reached for The Palestine Post. He had more reasons than he could list for loving her. She was intelligent and beautiful, calm and good. She was a healer of children. She made him a whole person, by bridging his contending identities. Growing up, Dan had never been able to reconcile his desire for the cosmopolitan world his family left when they emigrated from Berlin and his love of the dusty, vibrant, holy city to which they had moved. Anna experienced no such contradiction. Though deeply cultured, she loved nothing more than the sun and the sand of the Judean Hills, and she was naturally gifted with the candor he and other Zionists worked to cultivate. He recalled his first glimpse of the woman who would become his wife, in the Widener Library at Harvard, her thumb and finger pinching her chin thoughtfully over a Hebrew textbook. He remembered the note he had written her in that language, slipping it across the oak desk: Are you interested in a Hebrew tutor? And the words she scribbled on the paper before pushing it back toward him: Only if he will go Dutch for dinner.

“We could both go and hear Gottfried play, if you like. I think Shmulik and Devorah might join us. You and Devorah really did get along like a burning barn.”

“A house on fire,” she corrected.

Even after six years spent studying in Boston, Dan was still more comfortable speaking German and Hebrew. He liked to hear his American wife’s laid-back accent, though, and consequently spoke English to her all the time. “A house on fire,” Dan repeated. “Yes, you got on like a house on fire, for the ten minutes Shmulik spared to attend the reception. If you think you’ve been busy, imagine what it’s been like for him. Every time there’s a terror attack the Old Man wants to know why Shmulik didn’t see it coming.”

“That’s your fault. The more Jews you bring over from Germany, the angrier it makes the Arabs.”

“You can’t please everyone. Not the Old Man, that’s for sure.”

“You’re the only one capable of pleasing David Ben-Gurion. No one else could do what you do in Berlin.”

Dan let the hot water rush over his hands in

the sink. Berlin. He shut his eyes. It felt as though the lives of Germany’s Jews were sweeping through his hands, spilling down the drain where they were forever beyond his grasp. He went on regular trips to the German capital as head of the Palestine Emigration Office, a body recognized since 1933 by the Nazis as part of the deal with Hitler’s underlings known as the Transfer Agreement. The Nazis allowed departing Jews to keep most of their property, as long as they left for Palestine. If they went elsewhere, they were robbed of almost everything. Hitler wanted the Jews out of Europe, where he intended to create his Aryan empire.

Ben-Gurion caught hell for signing a deal with the Nazis, and Dan was accustomed to being called ugly names by Zionist leaders for his role in facilitating these emigrations. But the Jews he brought to Palestine were no longer beaten up by Brownshirts or kicked out of their jobs because of their race, the way their brethren who remained in Germany were. That was what kept him going.

He turned off the water and came into the living room. “Dishes all done.” He wedged himself next to Anna and kissed her silky black hair.

“There’s no room, you oaf,” she laughed.

“I know.” Dan rubbed the back of her neck. “But I hardly see you these days. I didn’t want to be all the way over there.”

“In Berlin?”

He pointed across the room. “On the couch.”

She giggled. They kissed.

“How many was it this time?” she said.

“Two thousand. It took a lot of arranging.” He frowned and looked down.

She touched his chin. “I’m sorry. I shouldn’t talk about your work when we were just going to—”

“It’s only that it’s never going to be enough. Never enough.”

The telephone rang. It was Shmulik Shoham. “Dan. Is this a bad time?”

“It was a good time until you called,” said Dan. “Go away.”

“Okay, okay. The Old Man wants you over at his house right now. You won’t believe the developments. Absolutely mind-blowing.”

“Can’t it wait till morning?”

“See you over there. Bye.”

Anna stretched out on the armchair and picked up a paperback. “I don’t need you. I have other men in my life. Hercule Poirot will keep me company.”

“I’ll see you in thirty years, when I’m retired.” With a last, lingering stroke of her hair, Dan set out into the cool Jerusalem night.

Within five minutes he was at Ben-Gurion’s home. The Old Man’s wife opened the door, wiping her hands on her flowered apron. Paula Ben-Gurion was a daunting woman, with a petulant chin and suspicious eyes. She was as short and powerful as her husband. Her intimidation was employed to protect him.

“Tea?” she asked. It was somewhere between a question and a command.

Dan stepped inside. “Coffee. Thank you.”

“He’s in the study with Shoham.” She shuffled off to the kitchen.

Chapter 2

The room was very warm. Ben-Gurion was examining a piece of board with strips of paper pasted onto it. Sitting at his desk, he wore his usual shapeless woolen dressing gown and a thick red scarf. Shmulik stood stiffly by his side—too controlled, Dan thought, as though he concealed an enormous restlessness.

“Sit down.” Ben-Gurion’s chill made his voice raspy.

Dan removed a heap of books from the simple chair by the desk and placed them among others on the floor. The study was crammed with volumes stacked in corners and jammed onto shelves. Paula waddled in and placed a glass of hot tea with honey and lemon in front of her husband. She brought coffee for the others. “He’s still fighting off a cold,” she cautioned. “Don’t keep him long.”

“You think that’s up to me?” Dan smiled.

In his early fifties, Ben-Gurion was thick-set, squat, and heavy-jowled. His small, shrewd eyes, beetling eyebrows, and bristly white hair gave him a pugnacious look, and indeed he was argumentative and cantankerous in the extreme. He was also not given to formality. He had yet to look at Dan. He slipped a cube of sugar into his mouth and took a noisy slurp of tea, his eyes still fixed on the page before him. “How did you say this turned up? Where exactly did you find it?”

Shmulik reached his fingertips into his light brown beard, as though the paper had emerged from within it. “In Professor Warrendale’s room at the King David Hotel.”

Ben-Gurion glanced up at him.

“In the wastepaper basket.” Shmulik gave the Old Man a raffish shrug. “We have people on the hotel staff. They have access to the rooms of the members of the Royal Commission.”

“When did they find this?”

“A couple of nights ago. After a preparatory meeting for today’s council.”

Ben-Gurion’s voice rose, staccato and hoarse. “What kind of nonsense is this? Who gave them permission to pry in the bedrooms of high-ranking British officials? On whose authority was this done?”

Shmulik lost his smug grin and delivered an uncomfortable underling’s cough. “On my authority,” he said.

That was a pretty good act, Dan thought. You might actually think Shmulik was a little uncomfortable. He shook his head in admiration. Shmulik winked at him.

“I took every precaution,” Shmulik said. “Our people were out of the rooms long before the meeting ended. The British all went straight to dinner afterward, but I had our people leave even before that to avoid discovery.”

Ben-Gurion pointed at the paper on his desk. “And how do you know for sure this belongs to Warrendale?”

“It’s his handwriting.”

The Old Man sniffed and sipped his tea. Dan noticed that Ben-Gurion didn’t bother to ask how Shmulik recognized the handwriting. His outrage had really been about authority, not security.

“Dan, what do we know of this Warrendale?” Ben-Gurion asked. “I don’t mean his official biography. I’ve seen that. I mean what do we really know about him?”

One of the few British officials who can look at a Jew or an Indian and see a human being, Dan thought. “I used to attend his lectures on government and colonial history. He was a visiting fellow at Harvard when I was doing my doctorate. He is, by far, the best brain on the Royal Commission.”

“But is he just an academic or is he also political? Are his feet on the ground? Does he live in the real world?”

“He’s a highly respected consultant to Whitehall. On matters to do with the workings of government, the structure of states, what creates a nation.”

“What’s that supposed to mean—‘what creates a nation’?”

You mean, what does Warrendale think it means? Dan thought. He knew exactly what Ben-Gurion would have meant by it. “It means, what are the minimal affinities necessary to enable diverse groups to come together to form a nation. Is there a coherent principle that explains how groups make the choice between union and separation?”

The Old Man, thoroughly fed up with his cold, griped, “I wish you’d speak simple Hebrew. We’re not at Harvard, we’re in my study.”

Dan looked about him at the bare walls and Spartan furniture, at the shelves of books in Russian, Polish, and Yiddish. No, we’re certainly not at Harvard, he mused. When he had been there, the fact that Harvard was not Jerusalem had been part of its appeal. In Boston he had found himself in a cultural center, away from the boorishness affected by many of the refugees from European gentility he knew at home, in Palestine.

He forced his mind back to the present. To Ben-Gurion. “I’ll give you an example. Last year, when there were those terrible riots in northern India between the Hindus and the Muslims, the British India Office asked Warrendale for his long-term assessment. His conclusion was that, given the contrasting and conflicting interests between the two groups, the only chance of peace was separation. He advocated partition.”

Ben-Gurion raised his head, as though finally Dan had said something interesting. “Partition?”

“Into two separate states. Northern India to the Muslims, the rest to the Hindus. Whitehall kep

t it all very hush-hush, but in one of his lectures Warrendale gave us a hint that let us know where they stood. He suggested that, while it may take some time to create the right circumstances for partition in India, most of Britain’s top echelons agree with him. So I can tell you now that whatever Warrendale has to say about us here in Palestine, Downing Street will listen, even if they don’t like what they hear.”

Dan pointed at the page lying in front of Ben-Gurion, the strips of ripped up paper pasted together on the cardboard. “I don’t know what Shmulik’s jigsaw puzzle says, but if Warrendale wrote it, we should take it seriously.”

Ben-Gurion glared at the page between his fingertips. Dan moved around the desk. Shmulik stepped aside to let him get closer.

It was a roughly sketched, pencil-drawn map of Palestine, shaded in different colors and crisscrossed with demarcation lines. One delineated the coastal plain and much of the northern territory. It was crayoned in green. Another patch, including all of the Negev and most of the mountainous territory west of the River Jordan, was colored blue. A corridor stretching from the sea to and around Jerusalem was crayoned red. Annotations filled the margins, written in tight, illegible scribbles and then crossed out, as if the author had experienced a hasty change of mind. The Royal Commission was supposed to figure out how Britain should unload the territory over which it had ruled for sixteen years at the behest of the League of Nations. Ever since the commissioners had set foot in the country, there had been rumors as to what solution they might eventually come up with—anything from autonomy to Swiss-style cantons. This rough map, evidently, was connected with one of those proposals.

“How are we supposed to make head or tail of this?” Ben-Gurion asked Shmulik. “You said it was absolutely urgent I see this tonight. Do we have transcripts? Any transmissions explaining exactly what it is?”

“That’s the problem,” said the Old Man’s intelligence chief. “There was a major hitch with the bugging system in the conference room. When the upholstery was cleaned the day before—”

The Ambassador

The Ambassador